... to bring you the Rap News.

Showing posts with label Politics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Politics. Show all posts

Tuesday, 8 February 2011

Saturday, 27 November 2010

Official News Sources and Citizen Journalists

Posted by

MONTAGU

Met Forced to Admit Mounted Police Charged Protesters at Wednesday's Anti-Cuts Demo

Scotland Yard has been forced to retract its statement about the use of mounted police charges during Wednesday's anti-Higher Education cuts demonstration. As reported in the Guardian, on Thursday a Met spokesperson categorically stated that "Police horses were involved in the operation, but that didn't involve charging the crowd."

Since then footage shot by a protester has surfaced that clearly shows mounted police charging without warning into a crowd containing school children, at least two mothers who had come to collect children and a pregnant woman.

Somehow the mainstream media managed to miss this and the other mounted police charge.

Citizen Journalists and Agenda Setting

Coming off the back of the citizen journalist footage that forced the Independent Police Complaints Commission to investigate whether the Met had misled the public over the death of Ian Tomlinson at the G20 protests in April last year, this highlights the value to protesters of on-scene video. After Ian Tomlinson was attacked by a policeman on his way home from work 'anonymous sources', 'eye-witnesses' and police sources were employed to set the agenda in the right-wing press. Sky News, for example: "Police said they were pelted with missiles believed to include bottles as they tried to save his life." Or this headline from the Evening Standard (now mysteriously disappeared from their website, captured here):

Without the video shot by protesters that clearly showed a police officer beating Tomlinson before pushing him to the ground this may have remained the accepted truth of the events that led to his death.

This demonstrates the power of authorities, including the police, to set the agenda in the mainstream media's reporting of events, as campaigning journalist Heather Brooke discusses in relation to the shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes in the video below.

Activist video and citizen journalism clearly has an increasing role to play in the countering of this sort of information control by authorities and institutions. Techniques first developed during the anti-road protest and environmental movements of the 1990s (see here from page 81, for example) are now, through mobile video technology, available to greater numbers of people and have been successful in shifting the public discourse about the policing of demonstrations, to a certain extent.

Viva Camcordistas!

Scotland Yard has been forced to retract its statement about the use of mounted police charges during Wednesday's anti-Higher Education cuts demonstration. As reported in the Guardian, on Thursday a Met spokesperson categorically stated that "Police horses were involved in the operation, but that didn't involve charging the crowd."

Since then footage shot by a protester has surfaced that clearly shows mounted police charging without warning into a crowd containing school children, at least two mothers who had come to collect children and a pregnant woman.

Somehow the mainstream media managed to miss this and the other mounted police charge.

Citizen Journalists and Agenda Setting

Coming off the back of the citizen journalist footage that forced the Independent Police Complaints Commission to investigate whether the Met had misled the public over the death of Ian Tomlinson at the G20 protests in April last year, this highlights the value to protesters of on-scene video. After Ian Tomlinson was attacked by a policeman on his way home from work 'anonymous sources', 'eye-witnesses' and police sources were employed to set the agenda in the right-wing press. Sky News, for example: "Police said they were pelted with missiles believed to include bottles as they tried to save his life." Or this headline from the Evening Standard (now mysteriously disappeared from their website, captured here):

Without the video shot by protesters that clearly showed a police officer beating Tomlinson before pushing him to the ground this may have remained the accepted truth of the events that led to his death.

This demonstrates the power of authorities, including the police, to set the agenda in the mainstream media's reporting of events, as campaigning journalist Heather Brooke discusses in relation to the shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes in the video below.

Activist video and citizen journalism clearly has an increasing role to play in the countering of this sort of information control by authorities and institutions. Techniques first developed during the anti-road protest and environmental movements of the 1990s (see here from page 81, for example) are now, through mobile video technology, available to greater numbers of people and have been successful in shifting the public discourse about the policing of demonstrations, to a certain extent.

Viva Camcordistas!

Friday, 12 November 2010

Who Are the Thugs?

Posted by

MONTAGU

Montagu’s Daughter would like to publicly condemn the behaviour of a small minority of anti-social yobs. The actions of these thugs do not represent the wishes of the vast majority of people in this country. It is a shame that these outside agitators have managed to hijack the democratic process for their own ends.

Let's hope that the media will not be distracted from focussing on the real issues.

Saturday, 2 October 2010

10:10 No Pressure Video: The Backlash

Posted by

MONTAGU

The Richard Curtis directed 10:10 campaign video No Pressure has prompted a furious backlash from climate change deniers.

Yesterday evening the 10:10 campaign issued the following statement:

Sorry.

Today we put up a mini-movie about 10:10 and climate change called 'No Pressure’.

With climate change becoming increasingly threatening, and decreasingly talked about in the media, we wanted to find a way to bring this critical issue back into the headlines whilst making people laugh. We were therefore delighted when Britain's leading comedy writer, Richard Curtis - writer of Blackadder, Four Weddings, Notting Hill and many others – agreed to write a short film for the 10:10 campaign. Many people found the resulting film extremely funny, but unfortunately some didn't and we sincerely apologise to anybody we have offended.

As a result of these concerns we've taken it off our website. We won't be making any attempt to censor or remove other versions currently in circulation on the internet.

We'd like to thank the 50+ film professionals and 40+ actors and extras and who gave their time and equipment to the film for free. We greatly value your contributions and the tremendous enthusiasm and professionalism you brought to the project.

At 10:10 we're all about trying new and creative ways of getting people to take action on climate change. Unfortunately in this instance we missed the mark. Oh well, we live and learn.

Onwards and upwards,

Franny, Lizzie, Eugenie and the whole 10:10 team

Criticism

Montagu spent a bit of time this morning scouring the interweb to get a feel for the criticisms of the No Pressure film. The general line of argument is something like "eco-fascists want to explode CHILDREN who don't agree with them" which represents a massive sense of humour FAIL on a film that was clearly meant to be a joke. Rather than reproduce the more ludicrous criticisms here lets take what can possibly be defined as the more "sophisticated" end of the climate denier spectrum as an example.

James Delingpole is a climate change denier and occasional Telegraph journalist that has been described by George Monbiot as specialising in "ill-informed viciousness provided for free by trolls on comment threads everywhere, but raised by an order of magnitude."

Delingpole argues that "With No Pressure, the environmental movement has revealed the snarling, wicked, homicidal misanthropy beneath its cloak of gentle, bunny-hugging righteousness."

Snarling, wicked, homicidal misanthropy? The extent to which the criticisms of the film reveal the hysteria of climate change deniers is entirely predictable. More surprising is the speed at which the 10:10 campaign capitulated to this, clearly deciding that No Pressure had become a propaganda own-goal in the space of a few hours. This shows the effectiveness of the climate change deniers at setting the agenda in online discourse.

However, it may also reveal some of the limits of the 10:10 campaign: the attempt to package a message about climate action in a simple, acceptable, a-political way. Perhaps the speed at which the campaign had been taken up in the mainstream - celebrity endorsements, Sony, David Cameron and so on - had given them the confidence that they had their finger on the Zeitgeist? The No Pressure film itself has a simple message - everyone should do their bit - and packages it with a mixture of light-hearted shock and celebrity endorsement. The negative response - removing and, for a time, attempting to suppress the video - demonstrates how this tactic can run into problems, shying away from genuine conflict at the first sign. Maybe they should have stuck to their guns a bit more and given the film some time to reach the right people? Or maybe made a stronger political argument about the obstacles to climate change action? You are never going to persuade hysterical climate change deniers like Delingpole, a man who lists his "likes" on his blog as "Margaret Thatcher; Ronald Reagan; English tradition; the American Way". I'd suggest exploding him.

Yesterday evening the 10:10 campaign issued the following statement:

Sorry.

Today we put up a mini-movie about 10:10 and climate change called 'No Pressure’.

With climate change becoming increasingly threatening, and decreasingly talked about in the media, we wanted to find a way to bring this critical issue back into the headlines whilst making people laugh. We were therefore delighted when Britain's leading comedy writer, Richard Curtis - writer of Blackadder, Four Weddings, Notting Hill and many others – agreed to write a short film for the 10:10 campaign. Many people found the resulting film extremely funny, but unfortunately some didn't and we sincerely apologise to anybody we have offended.

As a result of these concerns we've taken it off our website. We won't be making any attempt to censor or remove other versions currently in circulation on the internet.

We'd like to thank the 50+ film professionals and 40+ actors and extras and who gave their time and equipment to the film for free. We greatly value your contributions and the tremendous enthusiasm and professionalism you brought to the project.

At 10:10 we're all about trying new and creative ways of getting people to take action on climate change. Unfortunately in this instance we missed the mark. Oh well, we live and learn.

Onwards and upwards,

Franny, Lizzie, Eugenie and the whole 10:10 team

Criticism

Montagu spent a bit of time this morning scouring the interweb to get a feel for the criticisms of the No Pressure film. The general line of argument is something like "eco-fascists want to explode CHILDREN who don't agree with them" which represents a massive sense of humour FAIL on a film that was clearly meant to be a joke. Rather than reproduce the more ludicrous criticisms here lets take what can possibly be defined as the more "sophisticated" end of the climate denier spectrum as an example.

James Delingpole is a climate change denier and occasional Telegraph journalist that has been described by George Monbiot as specialising in "ill-informed viciousness provided for free by trolls on comment threads everywhere, but raised by an order of magnitude."

Delingpole argues that "With No Pressure, the environmental movement has revealed the snarling, wicked, homicidal misanthropy beneath its cloak of gentle, bunny-hugging righteousness."

Snarling, wicked, homicidal misanthropy? The extent to which the criticisms of the film reveal the hysteria of climate change deniers is entirely predictable. More surprising is the speed at which the 10:10 campaign capitulated to this, clearly deciding that No Pressure had become a propaganda own-goal in the space of a few hours. This shows the effectiveness of the climate change deniers at setting the agenda in online discourse.

However, it may also reveal some of the limits of the 10:10 campaign: the attempt to package a message about climate action in a simple, acceptable, a-political way. Perhaps the speed at which the campaign had been taken up in the mainstream - celebrity endorsements, Sony, David Cameron and so on - had given them the confidence that they had their finger on the Zeitgeist? The No Pressure film itself has a simple message - everyone should do their bit - and packages it with a mixture of light-hearted shock and celebrity endorsement. The negative response - removing and, for a time, attempting to suppress the video - demonstrates how this tactic can run into problems, shying away from genuine conflict at the first sign. Maybe they should have stuck to their guns a bit more and given the film some time to reach the right people? Or maybe made a stronger political argument about the obstacles to climate change action? You are never going to persuade hysterical climate change deniers like Delingpole, a man who lists his "likes" on his blog as "Margaret Thatcher; Ronald Reagan; English tradition; the American Way". I'd suggest exploding him.

Thursday, 23 September 2010

RIP UKFC: Geoffrey Macnab's Obituary of the UK FIlm Council

Posted by

MONTAGU

Geoffrey Macnab gives his obituary to the UK Film Council in October’s Sight and Sound.

This piece is worth a read for the insight it sheds on the debates that took place when the UK Film Council was formed, particularly the elusive desire for a sustainable, large-scale UK film industry.

As Macnab says, “the furore over the announcement [of the closure of the UK Film Council] underlines just how dependent on public funding the British film industry remains. It also reminds us how bitter the debates about public film policy have always been.”

He continues:

“We’re now at the end of a cycle. The UKFC is faced with abolition and the public film-funding model will almost certainly have to be redesigned. It was telling that in April 2010 the UKFC announced that its current chairman Tim Bevan would chair a think tank to identify ways of ‘growing UK companies of scale’. This, of course, was exactly the goal back in 1997, when the government awarded the three lottery-backed franchises worth more than £90 million over six years. The truth is that in 2010, over half of independent production companies are loss-making.”

The goal of a self-sustaining film industry is no more realistic now than it was back in 1998, or 1968 for that matter. The question is now, as it was then, how to sustain film-making in this country.

Any ideas let me – or Jeremy Hunt – know.

Tweet

This piece is worth a read for the insight it sheds on the debates that took place when the UK Film Council was formed, particularly the elusive desire for a sustainable, large-scale UK film industry.

As Macnab says, “the furore over the announcement [of the closure of the UK Film Council] underlines just how dependent on public funding the British film industry remains. It also reminds us how bitter the debates about public film policy have always been.”

He continues:

“We’re now at the end of a cycle. The UKFC is faced with abolition and the public film-funding model will almost certainly have to be redesigned. It was telling that in April 2010 the UKFC announced that its current chairman Tim Bevan would chair a think tank to identify ways of ‘growing UK companies of scale’. This, of course, was exactly the goal back in 1997, when the government awarded the three lottery-backed franchises worth more than £90 million over six years. The truth is that in 2010, over half of independent production companies are loss-making.”

The goal of a self-sustaining film industry is no more realistic now than it was back in 1998, or 1968 for that matter. The question is now, as it was then, how to sustain film-making in this country.

Any ideas let me – or Jeremy Hunt – know.

Tweet

Wednesday, 22 September 2010

Climate Change Activism Debate: Jamie Henn vs George Monbiot

Posted by

MONTAGU

Is this the start of a major debate within the climate change activist community? Veteran activist and commentator George Monbiot has been taken to task by the co-founder of climate change campaigning website 350.org, Jamie Henn. The debate so far is interesting, not only because it may be the beginning of a debate within the climate change activist community in general, but also because of what it suggests about media strategy and tactics in the fight against global warming - or more specifically, the fight to get governments to act over global warming. To explain...

Henn's article in the Huffington Post attacks an article of Monbiot's on Guardian.co.uk. In the original, Monbiot discussed the poor prospects of any sort of meaningful deal on climate change at the upcoming summit in Mexico in December. Monbiot - not being one to mince his words - argues that, with the failure of Copenhagen and the impending expiration of the Kyoto Protocol, "there is not a single effective instrument for containing man-made global warming anywhere on earth. The response to climate change, which was described by Lord Stern as 'a result of the greatest market failure the world has seen', is the greatest political failure the world has ever seen."

It's not hard to see why Henn would take this personally. 350.org, founded last year, grew from the Step it Up campaign founded by Bill McKibben in 2007. It exists, according to their website, in order to "create a grassroots movement connected by the web and active all over the world. We will focus on the systemic barriers to climate solutions, changing political dynamics whenever possible. At the same time, we'll get to work implementing real climate solutions in our communities, demonstrating the benefits of moving to a clean energy economy." Just the sort of instrument that George finds lacking in the current Green Movement, then.

To this Henn replies: "I think there is an instrument, but it isn't policy prescriptions or solar panels: it's the Internet." Henn continues: "Thankfully, there's a new movement that's been building up outside and inside the established environmental groups. All around the world, there's a new set of Young (twittering) Turks that are shaking up the status quo and offering a new way forward."

This debate raises questions about the centrality of new media to contemporary political activism, especially within the environmental movement. The 10:10 campaign, founded by McLibel and Age of Stupid director Franny Armstrong, is a good example of the strengths and limitations of this brand of Internet activism. The 10:10 campaign proposes a global day of action on the 10th October 2010 and the idea quickly spread across the world through the power of the Internet. At the same time, beyond creating press coverage, giving celebrities opportunities to demonstrate their green credentials and persuading people to recycle, its potential as a political force is unclear. In Britain it is so radical that David Cameron signed the British government up for it like a shot. How much of an effective or lasting impact will the campaign have on October the 11th?

350.org states that "we think the voice of ordinary people will be heard, if it's loud enough." But without an effective political force to channel that voice the danger, surely, is that it will be ignored among thousands of other decentralised and local actions. The Internet may be a useful tool to spread and coordinate activities, but it is surely a mistake to see it of itself as an effective instrument for containing man-made global warming. Monbiot asks "So what do we do now?" Hyperbole aside, Henn is forced to answer "I don't really know either."

Henn finishes by asking "we're doing our work, what about you?" This seems a bit rich considering Monbiot's record: founder of The Land is Ours campaign, banned from Indonesia and so on. While he can be a polarising figure his commitment to fighting climate change and finding effective solutions and strategies cannot be denied. Further, he has always championed direct action alongside strategies that aim to work within established political channels.

It will be interesting to see how this conversation pans out.

Finally, to do my bit and spread the word, the 350.org video:

Tweet

Henn's article in the Huffington Post attacks an article of Monbiot's on Guardian.co.uk. In the original, Monbiot discussed the poor prospects of any sort of meaningful deal on climate change at the upcoming summit in Mexico in December. Monbiot - not being one to mince his words - argues that, with the failure of Copenhagen and the impending expiration of the Kyoto Protocol, "there is not a single effective instrument for containing man-made global warming anywhere on earth. The response to climate change, which was described by Lord Stern as 'a result of the greatest market failure the world has seen', is the greatest political failure the world has ever seen."

It's not hard to see why Henn would take this personally. 350.org, founded last year, grew from the Step it Up campaign founded by Bill McKibben in 2007. It exists, according to their website, in order to "create a grassroots movement connected by the web and active all over the world. We will focus on the systemic barriers to climate solutions, changing political dynamics whenever possible. At the same time, we'll get to work implementing real climate solutions in our communities, demonstrating the benefits of moving to a clean energy economy." Just the sort of instrument that George finds lacking in the current Green Movement, then.

To this Henn replies: "I think there is an instrument, but it isn't policy prescriptions or solar panels: it's the Internet." Henn continues: "Thankfully, there's a new movement that's been building up outside and inside the established environmental groups. All around the world, there's a new set of Young (twittering) Turks that are shaking up the status quo and offering a new way forward."

This debate raises questions about the centrality of new media to contemporary political activism, especially within the environmental movement. The 10:10 campaign, founded by McLibel and Age of Stupid director Franny Armstrong, is a good example of the strengths and limitations of this brand of Internet activism. The 10:10 campaign proposes a global day of action on the 10th October 2010 and the idea quickly spread across the world through the power of the Internet. At the same time, beyond creating press coverage, giving celebrities opportunities to demonstrate their green credentials and persuading people to recycle, its potential as a political force is unclear. In Britain it is so radical that David Cameron signed the British government up for it like a shot. How much of an effective or lasting impact will the campaign have on October the 11th?

350.org states that "we think the voice of ordinary people will be heard, if it's loud enough." But without an effective political force to channel that voice the danger, surely, is that it will be ignored among thousands of other decentralised and local actions. The Internet may be a useful tool to spread and coordinate activities, but it is surely a mistake to see it of itself as an effective instrument for containing man-made global warming. Monbiot asks "So what do we do now?" Hyperbole aside, Henn is forced to answer "I don't really know either."

Henn finishes by asking "we're doing our work, what about you?" This seems a bit rich considering Monbiot's record: founder of The Land is Ours campaign, banned from Indonesia and so on. While he can be a polarising figure his commitment to fighting climate change and finding effective solutions and strategies cannot be denied. Further, he has always championed direct action alongside strategies that aim to work within established political channels.

It will be interesting to see how this conversation pans out.

Finally, to do my bit and spread the word, the 350.org video:

Tweet

Sunday, 19 September 2010

Cultural Shock Doctrine Part Two - Hunt Attacks Progessive Cultural Policy

Posted by

MONTAGU

Jeremy-culture-vandal-Hunt (who is fast becoming a favourite subject of this Blog) used his speech at the Media Festival Arts in London to reiterate his “long term commitment to the arts sector”. Hunt talked of sharing pain, future growth, blah blah blah...

But what shape is this sector going to take? Hunt also took the opportunity to take a swipe at instrumental aspects of cultural funding under New Labour, according to The Mail:

“Public money will no longer be given to arts organisations simply because they hire a high proportion of women or ethnic minorities”. The “days of securing taxpayer funds purely by box ticking – getting cash simply because a diversity target has been hit – are now over.”

This suggests a number of things about the politics of the cultural shock doctrine.

Firstly, the idea that organisations were hiring a high proportion of women or ethnic minorities to get cash is laughable – the problem has always been that were not hiring a fair proportion, ie one that reflects the population as a whole, the local area or the audience. Instrumental policies, where they actually existed, were designed to address systemic racism and sexism by increasing diversity to more equal levels. Attacks on policies that attempt to make the cultural sector a more equal place are, of course, quite natural Tory territory.

Secondly, there has been a popular and sector perception of this sort of reverse discrimination going back to the cultural industries days of the Greater London Council in the 1980s. However, the extent to which this ever informed creative industries policies in their post-1997 incarnation is debatable (The Mail can only give the example of one book of ethnic minority poetry, although, to be fair, this may represent poor journalism). New Labour were able, through the discourse of the creative industries, to draw together the genuinely politically progressive sections of the cultural sector that developed in the 1980s behind the idea of market-led diversity. To take an example from film policy:

“Diversity is both a catalyst for creativity and is key to the success of the UK film sector. However, the profile of the sector’s workforce shows it has a long way to go before it can demonstrate that it is inclusive of the diversity of contemporary British society. Inevitably, this has a significant impact on the stories that are told, the way they are told on screen, the levels of access to film for potential audiences and, in terms of content and portrayal, the images of Britain and the concepts of “Britishness” around the globe.” (Report here, page 5)

This is a reflection of a cultural policy that managed to align a progressive cultural politics with commercial interests. While this discourse paid lip-service to diversity, multi-culturalism and so on, its real focus was always the market. It therefore found it hard to interfere with areas of the market that worked but also happened to be white-male dominated. As a result, New Labour cultural policy was seemingly unable to make a case for diversity that is not based on commercial success; a moral or political argument, for instance. As mentioned in a previous post, after thirteen years of this, research has shown that the film industry is still inherently racist and sexist. Furthermore, in employment terms the cultural sector is more male dominated than the rest of the economy (63% compared to 53% - figure here, page 47). The idea that the last thirteen years were a bonanza in public funding for members of ethnic minorities and women regardless of talent or quality is a myth promoted by arseholes such as this one.

For the Tories, attacks on this sort of thinking are a coded way of attacking the principle of anything remotely politically progressive in cultural policy in general and clearly they are signalling that they are withdrawing support and political influence from the liberal cultural intelligentsia. Further, this works to deflect criticism from the cultural shock doctrine – the cuts in cultural funding are about withdrawing the tax burden created by rampant political correctness and restoring cultural authority to the white middle-classes, as opposed to hamstringing the cultural sector. As Kristine Landon-Smith argues in the Newstateman, “we are seeing a retrogressive new conservatism at work.”

At the same time, this ties into a genuine hostility to the cultural management mechanisms favoured by New Labour – the hysterical emphasis on targets, application forms, report-writing; a bureaucratic centralised system which effectively stifled autonomy.

New Labour came to power in 1997 with a relatively coherent cultural policy developed during time in opposition with clear differences to their predecessors. Cultural conservatism was to be dispelled in favour of modernisation; the heritage industries became creative industries. So far the ConDems have only demonstrated slash and burn dressed up as right wing dogma. We can undoubtedly expect more of this sort of thing in the coming months and years.

But what shape is this sector going to take? Hunt also took the opportunity to take a swipe at instrumental aspects of cultural funding under New Labour, according to The Mail:

“Public money will no longer be given to arts organisations simply because they hire a high proportion of women or ethnic minorities”. The “days of securing taxpayer funds purely by box ticking – getting cash simply because a diversity target has been hit – are now over.”

This suggests a number of things about the politics of the cultural shock doctrine.

Firstly, the idea that organisations were hiring a high proportion of women or ethnic minorities to get cash is laughable – the problem has always been that were not hiring a fair proportion, ie one that reflects the population as a whole, the local area or the audience. Instrumental policies, where they actually existed, were designed to address systemic racism and sexism by increasing diversity to more equal levels. Attacks on policies that attempt to make the cultural sector a more equal place are, of course, quite natural Tory territory.

Secondly, there has been a popular and sector perception of this sort of reverse discrimination going back to the cultural industries days of the Greater London Council in the 1980s. However, the extent to which this ever informed creative industries policies in their post-1997 incarnation is debatable (The Mail can only give the example of one book of ethnic minority poetry, although, to be fair, this may represent poor journalism). New Labour were able, through the discourse of the creative industries, to draw together the genuinely politically progressive sections of the cultural sector that developed in the 1980s behind the idea of market-led diversity. To take an example from film policy:

“Diversity is both a catalyst for creativity and is key to the success of the UK film sector. However, the profile of the sector’s workforce shows it has a long way to go before it can demonstrate that it is inclusive of the diversity of contemporary British society. Inevitably, this has a significant impact on the stories that are told, the way they are told on screen, the levels of access to film for potential audiences and, in terms of content and portrayal, the images of Britain and the concepts of “Britishness” around the globe.” (Report here, page 5)

This is a reflection of a cultural policy that managed to align a progressive cultural politics with commercial interests. While this discourse paid lip-service to diversity, multi-culturalism and so on, its real focus was always the market. It therefore found it hard to interfere with areas of the market that worked but also happened to be white-male dominated. As a result, New Labour cultural policy was seemingly unable to make a case for diversity that is not based on commercial success; a moral or political argument, for instance. As mentioned in a previous post, after thirteen years of this, research has shown that the film industry is still inherently racist and sexist. Furthermore, in employment terms the cultural sector is more male dominated than the rest of the economy (63% compared to 53% - figure here, page 47). The idea that the last thirteen years were a bonanza in public funding for members of ethnic minorities and women regardless of talent or quality is a myth promoted by arseholes such as this one.

For the Tories, attacks on this sort of thinking are a coded way of attacking the principle of anything remotely politically progressive in cultural policy in general and clearly they are signalling that they are withdrawing support and political influence from the liberal cultural intelligentsia. Further, this works to deflect criticism from the cultural shock doctrine – the cuts in cultural funding are about withdrawing the tax burden created by rampant political correctness and restoring cultural authority to the white middle-classes, as opposed to hamstringing the cultural sector. As Kristine Landon-Smith argues in the Newstateman, “we are seeing a retrogressive new conservatism at work.”

At the same time, this ties into a genuine hostility to the cultural management mechanisms favoured by New Labour – the hysterical emphasis on targets, application forms, report-writing; a bureaucratic centralised system which effectively stifled autonomy.

New Labour came to power in 1997 with a relatively coherent cultural policy developed during time in opposition with clear differences to their predecessors. Cultural conservatism was to be dispelled in favour of modernisation; the heritage industries became creative industries. So far the ConDems have only demonstrated slash and burn dressed up as right wing dogma. We can undoubtedly expect more of this sort of thing in the coming months and years.

Friday, 17 September 2010

Creative Industries are Bollocks - Podcast on Media Studies and Higher Education

Posted by

MONTAGU

Montagu came across this Podcast on the Culturalstudies website which may be of interest to anyone anticipating the destruction of Higher Education. US-based academic Toby Miller interviews Des Freedman and Natalie Fenton from Goldsmiths on the cuts being made to the sector and challenges facing media studies as a subject. This is an interesting discussion about the development and influence of the creative industries discourse.

The creative industries discourse is one mechanism through which media and cultural studies are being increasingly geared towards the perceived needs of industry and business. This is, of course, part of a wider political-economic process and linked to fashionable concepts of the post-industrial economy, the knowledge economy, the information society, and so on. It's important, therefore, to develop a sophisticated and piercing critique.

"It's bollocks" - Fenton.

In the second part of the interview Fenton and Freedman talk about their research which is also worth a listen if you are that way inclined.

The creative industries discourse is one mechanism through which media and cultural studies are being increasingly geared towards the perceived needs of industry and business. This is, of course, part of a wider political-economic process and linked to fashionable concepts of the post-industrial economy, the knowledge economy, the information society, and so on. It's important, therefore, to develop a sophisticated and piercing critique.

"It's bollocks" - Fenton.

In the second part of the interview Fenton and Freedman talk about their research which is also worth a listen if you are that way inclined.

Thursday, 16 September 2010

Culture Vandals from Magdalen College

Posted by

MONTAGU

In a recent article, Evening Standard columnist Sasha Slater recounts her time at Magdalen College, Oxford. Magdalen College is, of course, the illustrious institution at the centre of the Laura Spence scandal of 2001. It is also the former College of no less than five members of the Cabinet including George Osborne, William Hague, Chris Huhne, Dominic Grieve and Jeremy-culture-vandal-Hunt.

Slater remembers:

“A drunken student (now a company director) swinging, Tarzan-like, out of the windows of the Junior Common Room gave an ancient sculpture of a greyhound a swipe with his feet and smashed it to smithereens on the flagstones below. Undaunted, the president of the college, who should have known better, borrowed a beautiful full-sized mirrored sculpture of a winged unicorn from the flamboyant artist Andrew Logan. This was erected amid great fanfares but only lasted a couple of weeks before the same student snapped its horn off. Andrew Logan's response was unprintable.”

I wonder if this is the sort of education that prepared the Culture Secretary to lead us through these tough economic times?

Slater remembers:

“A drunken student (now a company director) swinging, Tarzan-like, out of the windows of the Junior Common Room gave an ancient sculpture of a greyhound a swipe with his feet and smashed it to smithereens on the flagstones below. Undaunted, the president of the college, who should have known better, borrowed a beautiful full-sized mirrored sculpture of a winged unicorn from the flamboyant artist Andrew Logan. This was erected amid great fanfares but only lasted a couple of weeks before the same student snapped its horn off. Andrew Logan's response was unprintable.”

I wonder if this is the sort of education that prepared the Culture Secretary to lead us through these tough economic times?

Tuesday, 14 September 2010

Cultural Shock Doctrine: Arts Funding Cuts and Neoliberalism

Posted by

MONTAGU

Further to a previous post, the cuts in arts funding in the UK are starting to take effect. The Department of Culture, Media and Sport is expected to be one of the hardest hit in the upcoming spending review and is anticipating cuts of up to 40%. Culture-vandal Jeremy Hunt already announced the closure of the UK Film Council. According to Trisha Andres in the Guardian, we can now add to this list arts services and schemes specifically targetted to the young such as the Arts Journalist Bursary Scheme and the Find Your Talent Scheme.

Along with cuts to University places, apprenticeships and jobs the ConDems cuts are already hitting young people hard. Unemployment among the young (under-18s) is already 33% and for those without GCSEs it is as high as 50%. 77% of the decline in employment has been felt by young people (under-24s). Figures here.

On the other hand we have corporate culture-vultures waiting in the wings for their share of reconstructed neoliberal art once the flames die down. For example, Rena De Sisto at Merrill Lynch - who has the Sith-like job title of Global Arts and Culture Executive - has argued that:

"The government proposes that the arts community adopt the US-based approach to arts funding, with less dependence upon public and more upon private funding sources. In fact, the British arts community already has a tradition of private philanthropic and corporate funding, so the difference with the US is really one of degree. And while the US may be further along the curve, with its longer, more comfortable relationship with private funding for the arts, in both nations the arts sector can benefit from new approaches to working with corporations. Similarly, many types of companies can and do benefit greatly from supporting the arts. But some fundamental changes need to occur to unlock this opportunity."

De Sisto argues that the days of public support are over and that arts organisations must allow companies to "extract sound business benefits, such as access for employees, brand visibility and client outreach opportunities." Doesn't sound much like a culture to me.

This is, of course, nothing new. The Thatcherite attack on the cultural welfare state was always predicated on the wider attack on the post-War social democratic settlement and this represents the latest phase of neoliberal restructuring. For example, Richard Luce was Minister for the Arts in Thatcher's government when he made this statement in 1987:

“there are still too many in the arts world who have yet to be weaned away from the welfare state mentality - the attitude that the taxpayer owes them a living. Many have not yet accepted the challenge of developing plural sources of funding. They give the impression of thinking that all other sources of funding are either tainted or too difficult to get. They appear not to have grasped that the collectivist mentality of the sixties and seventies is out of date.” (Quoted here, page 30)

This again shows the need for opponents of cuts in arts and cultural funding to join the dots and link-up with the wider campaigns to defend public services. And ideally this would be a grassroots campaign that is led by the people who have most to lose from a barren neoliberal-corporate culture, not by Damien Hirst.

Along with cuts to University places, apprenticeships and jobs the ConDems cuts are already hitting young people hard. Unemployment among the young (under-18s) is already 33% and for those without GCSEs it is as high as 50%. 77% of the decline in employment has been felt by young people (under-24s). Figures here.

On the other hand we have corporate culture-vultures waiting in the wings for their share of reconstructed neoliberal art once the flames die down. For example, Rena De Sisto at Merrill Lynch - who has the Sith-like job title of Global Arts and Culture Executive - has argued that:

"The government proposes that the arts community adopt the US-based approach to arts funding, with less dependence upon public and more upon private funding sources. In fact, the British arts community already has a tradition of private philanthropic and corporate funding, so the difference with the US is really one of degree. And while the US may be further along the curve, with its longer, more comfortable relationship with private funding for the arts, in both nations the arts sector can benefit from new approaches to working with corporations. Similarly, many types of companies can and do benefit greatly from supporting the arts. But some fundamental changes need to occur to unlock this opportunity."

De Sisto argues that the days of public support are over and that arts organisations must allow companies to "extract sound business benefits, such as access for employees, brand visibility and client outreach opportunities." Doesn't sound much like a culture to me.

This is, of course, nothing new. The Thatcherite attack on the cultural welfare state was always predicated on the wider attack on the post-War social democratic settlement and this represents the latest phase of neoliberal restructuring. For example, Richard Luce was Minister for the Arts in Thatcher's government when he made this statement in 1987:

“there are still too many in the arts world who have yet to be weaned away from the welfare state mentality - the attitude that the taxpayer owes them a living. Many have not yet accepted the challenge of developing plural sources of funding. They give the impression of thinking that all other sources of funding are either tainted or too difficult to get. They appear not to have grasped that the collectivist mentality of the sixties and seventies is out of date.” (Quoted here, page 30)

This again shows the need for opponents of cuts in arts and cultural funding to join the dots and link-up with the wider campaigns to defend public services. And ideally this would be a grassroots campaign that is led by the people who have most to lose from a barren neoliberal-corporate culture, not by Damien Hirst.

Monday, 13 September 2010

Sunday, 12 September 2010

Defend the Arts Animation by David Shrigley

Posted by

MONTAGU

Defend the arts video by David Shrigley.

Friday, 10 September 2010

This is England 86: Politics and Nostalgia Part One

Posted by

MONTAGU

Montagu has been eagerly awaiting director Shane Meadows’ first foray into television with This is England 86, a four-part spin-off to his outstanding 2006 film This is England. The first part screened on Channel Four on Tuesday night to generally positive reviews (the Telegraph described it as “astonishingly good”) and a solid audience share. This is quality British television in the making.

Meadows is an interesting director; a maverick of new British cinema, his films blend the irreverent ‘underclass’ humour that was put into effect so successfully in Shameless with a sense of genuine commitment to working class community, culture and experience, particularly from the perspective of children and young people. This means that his often biting and ludicrous satire very rarely becomes patronising. Meadows stands firmly inside the tent pissing out.

This is England contained the thematic preoccupations that have defined all Meadows’ films: the exploration of marginalised and periphery working class communities and experience; masculinity, childhood and adolescence. However, it also marked a new, more explicitly politicised edge to his films, set at the height of Thatcherite jingoism during the Falklands war and critiquing far-Right politics. The final scene where Shaun throws a Union Jack into the sea was a marvellous cinematic antidote to the popular nationalism and racism given space to expand by New Labour’s foreign and domestic policies of populist racism.

Andrew Higson, in a discussion of heritage costume dramas of the 1980s, identifies a tension between the visual spectacle of nostalgia and a more politicised social critique. From this point of view nostalgia, as one of the central genres or modes in British film, can be seen as inherently conservative and in opposition to the more progressive traditions of realistic British cinema which have tended to focus on the here and now. Of course, this opposition has a long history in socialist politics in which we can see nostalgia allied with conservatism in trying to “role back the wheel of history” (in Marx’s phrase). This makes This is England 86 an interesting prospect politically. Does the nostalgia of the series undercut its potential to offer a social commentary on recession and unemployment in the present? Meadows himself clearly does not see any incompatibility:

“Not only did I want to take the story of the gang broader and deeper, I also saw in the experiences of the young in 1986 many resonances to now - recession, lack of jobs, sense of the world at a turning point.”

On the other hand, the appeal of the series might be found precisely in a depoliticised, backward facing nostalgia. For example, the preview event in Sheffield:

“For the creation and promotion of this event, Fuse Sport & Entertainment and film specialist elevenfiftyfive are collaborating to curate a live, interactive experience, taking fans back to 1986 where the cinema will be transformed into a working man’s social club, including a live performance by a local Ska band, free sausage rolls and monster munch to boot!”

From the evidence of the first part in the series, nostalgia for the 1980s has been placed more centrally than politics, particularly in terms of iconography - from soda streams to shell suits and scooters. At points this seemed clumsy and overbearing. On the other hand, the performances of Vicky McClure as Lol and Joe Gilgum as Woody were fantastic and a female central character is a well-needed departure from Meadows’ usual nearly exclusive focus on masculinity and men. We shall delay a final analysis of the political potential of nostalgia in This is England 86 until it has run in its entirety.

Watch this space.

Meadows is an interesting director; a maverick of new British cinema, his films blend the irreverent ‘underclass’ humour that was put into effect so successfully in Shameless with a sense of genuine commitment to working class community, culture and experience, particularly from the perspective of children and young people. This means that his often biting and ludicrous satire very rarely becomes patronising. Meadows stands firmly inside the tent pissing out.

This is England contained the thematic preoccupations that have defined all Meadows’ films: the exploration of marginalised and periphery working class communities and experience; masculinity, childhood and adolescence. However, it also marked a new, more explicitly politicised edge to his films, set at the height of Thatcherite jingoism during the Falklands war and critiquing far-Right politics. The final scene where Shaun throws a Union Jack into the sea was a marvellous cinematic antidote to the popular nationalism and racism given space to expand by New Labour’s foreign and domestic policies of populist racism.

Andrew Higson, in a discussion of heritage costume dramas of the 1980s, identifies a tension between the visual spectacle of nostalgia and a more politicised social critique. From this point of view nostalgia, as one of the central genres or modes in British film, can be seen as inherently conservative and in opposition to the more progressive traditions of realistic British cinema which have tended to focus on the here and now. Of course, this opposition has a long history in socialist politics in which we can see nostalgia allied with conservatism in trying to “role back the wheel of history” (in Marx’s phrase). This makes This is England 86 an interesting prospect politically. Does the nostalgia of the series undercut its potential to offer a social commentary on recession and unemployment in the present? Meadows himself clearly does not see any incompatibility:

“Not only did I want to take the story of the gang broader and deeper, I also saw in the experiences of the young in 1986 many resonances to now - recession, lack of jobs, sense of the world at a turning point.”

On the other hand, the appeal of the series might be found precisely in a depoliticised, backward facing nostalgia. For example, the preview event in Sheffield:

“For the creation and promotion of this event, Fuse Sport & Entertainment and film specialist elevenfiftyfive are collaborating to curate a live, interactive experience, taking fans back to 1986 where the cinema will be transformed into a working man’s social club, including a live performance by a local Ska band, free sausage rolls and monster munch to boot!”

From the evidence of the first part in the series, nostalgia for the 1980s has been placed more centrally than politics, particularly in terms of iconography - from soda streams to shell suits and scooters. At points this seemed clumsy and overbearing. On the other hand, the performances of Vicky McClure as Lol and Joe Gilgum as Woody were fantastic and a female central character is a well-needed departure from Meadows’ usual nearly exclusive focus on masculinity and men. We shall delay a final analysis of the political potential of nostalgia in This is England 86 until it has run in its entirety.

Watch this space.

Tuesday, 7 September 2010

Blacklisted the Movie

Posted by

MONTAGU

From the Reel News Facebook page:

First ever public showing of BLACKLISTED, the new documentary (15 mins) about the illegal Consulting Association blacklist containing personal details on 3213 building workers who had raised concerns about safety or unpaid wages. The secret database was used by multinational construction firms to prevent trade unionists from gaining employment. The blacklist is a continuation of a vindictive attitude by building firms towards un...ions going back many decades. The film shares first hand experience from 12 blacklisted workers (including Ricky Tomlinson) about their fight for justice.

After the film, blacklisted workers, Reel News, MPs and human rights experts will take questions and discuss the ongoing campaign against blacklisting and the implications for all trade unions today.

Chair: Steve Acheson (Blacklisted Electrician and UNITE Manchester Contracting Branch Secretary)

Speakers:

John McDonnell MP

Professor Keith Ewing (Institute of Employment Rights)

Shaun Dey (Reel News)

Chris Murphy (UCATT Executive Council)

plus Blacklisted building workers from UNITE and UCATT

Wednesday, 25 August 2010

Hollywood's Politics

Posted by

MONTAGU

There's a good interview with Matthew Alford over at the consistently excellent New Left Project website. Alford has just written a book on Hollywood films as propaganda for the American empire.

This is a longstanding and interesting debate: the extent to which Hollywood is dominated by whinging pinko liberals, as the American Right has it, or whether it is best understood as the ideological arm of American capitalism and imperialism. Or does it matter? Film studies has tied itself up in knots with this stuff for years, from the rejection of all film narrative as inherently reactionary which was fashionable in film theory circles in the 1970s and 1980s to the more recent drive to resuscitate and depoliticise the concept of entertainment.

As a useful antidote to the more ludicrous intellectual contortions that have attempted to make sense of film and politics, Alford puts it simply: "Nothing is ‘just a story’ – films are part of a socialisation process, just as we read Fairy Tales in part to help children make sense of the world. Of course, if someone asks you what article you’re reading in newspaper, it would be rather truculent to reply ‘It’s a propaganda piece consistent with establishment interests’. It would be more worthwhile though if you investigated the content of that article, identified its sources and what it omits, how it fits in with other material in the same newspaper, and so on. It’s the same with Hollywood – it does not suit corporate owners when audiences recognise the obscenity or the idiocy of the political messages they provide but this is best exposed systematically."

As such, Alford notes that "The US first declared a ‘War on Terror’ in 1985. Hollywood has stuck closely to Washington’s line ever since, including the trend for Islamist villains in the mid-1990s (True Lies, Executive Decision), as the ‘clash of civilisations’ theory was gaining traction. More recently, we have had movies like Munich, Back Hawk Down and The Kingdom that support the notion of Western benevolence in the quest to stamp out Islamic terrorism.

With regard to 9/11 itself, no major studio has thought to question the government’s narrative despite the incredible popularity of alternate takes on that day’s events. The Pentagon and the White House warmly embraced United 93 and a string of other similar films."

But Alford, what about all the exceptions? Doesn't Hollywood make many films that critique the myths of American capitalism and Empire?

"There are a few, but look what happens to them… Genuinely critical films such as John Cusack’s War, Inc and Brian de Palma’s Redacted opened in just a few dozen cinemas in New York and L.A. Disney told its subsidiary Miramax to ditch Fahrenheit 9/11, which led to Miramax’s bosses leaving to create a new company. CBS, NBC and ABC all refused to advertise Michael Moore’s DVD in between news programming. The pattern is familiar."

This looks like a solid, interesting and useful bit of research and Montagu can't wait to read it.

This is a longstanding and interesting debate: the extent to which Hollywood is dominated by whinging pinko liberals, as the American Right has it, or whether it is best understood as the ideological arm of American capitalism and imperialism. Or does it matter? Film studies has tied itself up in knots with this stuff for years, from the rejection of all film narrative as inherently reactionary which was fashionable in film theory circles in the 1970s and 1980s to the more recent drive to resuscitate and depoliticise the concept of entertainment.

As a useful antidote to the more ludicrous intellectual contortions that have attempted to make sense of film and politics, Alford puts it simply: "Nothing is ‘just a story’ – films are part of a socialisation process, just as we read Fairy Tales in part to help children make sense of the world. Of course, if someone asks you what article you’re reading in newspaper, it would be rather truculent to reply ‘It’s a propaganda piece consistent with establishment interests’. It would be more worthwhile though if you investigated the content of that article, identified its sources and what it omits, how it fits in with other material in the same newspaper, and so on. It’s the same with Hollywood – it does not suit corporate owners when audiences recognise the obscenity or the idiocy of the political messages they provide but this is best exposed systematically."

As such, Alford notes that "The US first declared a ‘War on Terror’ in 1985. Hollywood has stuck closely to Washington’s line ever since, including the trend for Islamist villains in the mid-1990s (True Lies, Executive Decision), as the ‘clash of civilisations’ theory was gaining traction. More recently, we have had movies like Munich, Back Hawk Down and The Kingdom that support the notion of Western benevolence in the quest to stamp out Islamic terrorism.

With regard to 9/11 itself, no major studio has thought to question the government’s narrative despite the incredible popularity of alternate takes on that day’s events. The Pentagon and the White House warmly embraced United 93 and a string of other similar films."

But Alford, what about all the exceptions? Doesn't Hollywood make many films that critique the myths of American capitalism and Empire?

"There are a few, but look what happens to them… Genuinely critical films such as John Cusack’s War, Inc and Brian de Palma’s Redacted opened in just a few dozen cinemas in New York and L.A. Disney told its subsidiary Miramax to ditch Fahrenheit 9/11, which led to Miramax’s bosses leaving to create a new company. CBS, NBC and ABC all refused to advertise Michael Moore’s DVD in between news programming. The pattern is familiar."

This looks like a solid, interesting and useful bit of research and Montagu can't wait to read it.

Wednesday, 11 August 2010

Join the Dots...

Posted by

MONTAGU

Four items caught Montagu's eye this week.

Firstly, a change in growth forecasts from the Bank of England shows that "Recent business surveys have suggested consumer and business confidence remain fragile and some experts are predicting a double-dip recession. Companies in the dominant services sector say they are losing important public sector work and households are cutting back spending as they brace for job cuts."

Public sector austerity is not putting us on the road to recovery.

Secondly, a report in The Independent: "research by the employment consultancy Hewitt New Bridge Street shows that despite the feeble economic recovery executive pay at Britain's FTSE 100 companies continues to soar. The median total remuneration for the highest paid directors in FTSE 100 companies is now just below £3m. It has risen from £2.5m a year ago, even as leading companies have been implementing massive job cuts."

It continues: "Unemployment has risen in the period covered to nearly 2.5 million people out of work, and the average pay increase across the country, including bonuses, was just 2.7 per cent in the year to May, according to the Office for National Statistics."

Related? This is just the beginning of the bite felt from the policies of Cameron's Big Society lie - the relative transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich.

What this is all really about is neatly explained in this little video posted on Lenin's Tomb:

Privatisation.

Finally, a useful summary of the Big Lie from Red Pepper.

Joining the dots between these things is important if people are to make sense of what the government is doing, what is at stake and how they can argue against it. It is well put by David Wearing at the New Left Project when he says that "there is (at least from the point of view of the public, rather than elite interest) no emergency requiring this budget. The emergency is the budget."

Firstly, a change in growth forecasts from the Bank of England shows that "Recent business surveys have suggested consumer and business confidence remain fragile and some experts are predicting a double-dip recession. Companies in the dominant services sector say they are losing important public sector work and households are cutting back spending as they brace for job cuts."

Public sector austerity is not putting us on the road to recovery.

Secondly, a report in The Independent: "research by the employment consultancy Hewitt New Bridge Street shows that despite the feeble economic recovery executive pay at Britain's FTSE 100 companies continues to soar. The median total remuneration for the highest paid directors in FTSE 100 companies is now just below £3m. It has risen from £2.5m a year ago, even as leading companies have been implementing massive job cuts."

It continues: "Unemployment has risen in the period covered to nearly 2.5 million people out of work, and the average pay increase across the country, including bonuses, was just 2.7 per cent in the year to May, according to the Office for National Statistics."

Related? This is just the beginning of the bite felt from the policies of Cameron's Big Society lie - the relative transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich.

What this is all really about is neatly explained in this little video posted on Lenin's Tomb:

Privatisation.

Finally, a useful summary of the Big Lie from Red Pepper.

Joining the dots between these things is important if people are to make sense of what the government is doing, what is at stake and how they can argue against it. It is well put by David Wearing at the New Left Project when he says that "there is (at least from the point of view of the public, rather than elite interest) no emergency requiring this budget. The emergency is the budget."

Tuesday, 27 July 2010

The End of the UK Film Council: A return to the 1980s?

Posted by

MONTAGU

Yesterday the ConDems announced their plans to abolish the UKFC as part of their more general policy of slash and burn in public services (Netribution has live commentary here). We imagine for many people it comes as a surprise to think of the UKFC as a public service, not least the executives judging by the salaries they paid themselves. They did everything they were supposed to: it wasn't subsidy, culture or art, but investment, economic development and sustainability. Judging by the reactions so far, the extent to which the UKFC came to represent the British film industry becomes apparent, as if nothing is imaginable without them.

This, then, is an opportunity to think through some 'old' arguments. Why, and in what way, should the government fund film? The UKFC and its advocates seem to be almost completely incapable of making an argument that does not come down to a commercial logic: we invest money into the film industry which has been a growth area of the UK economy. They always represented the perceived interests of the industry players more than the public, or most individual film-makers, who were required to work within a framework that emphasised commercial potential at the expense of everything else. Well, commercial logic has come back to bite them: propping up the banking sector is clearly more valuable to the economy than propping up the film industry. But defending public subsidy at a time like this requires arguments based on other reasons, cultural reasons, political reasons, moral reasons, for example. It is these arguments, more than any others, that can sustain opposition to the ConDems plans for the Big Society (which looks increasingly like 'there is no such thing as society') and judging by the comments on the 'Save the UKFC' Facebook group it is these arguments that motivate most people to defend the UKFC as well.

So is this the death of the UK film industry? A return to the bad old days of Thatcher and the almost complete collapse of British film production? The government's announcement is that it will establish a more direct relationship with the BFI and the Regional Screen Agencies are apprently safe, for the moment. This would seem to be a return to the state of things pre-UKFC with a modest film-culture infrastructure. But is the BFI now capable of fulfilling this role, particularly in terms of production?

The devil, as always, is in the detail. The key questions are: how much will overall subsidy be reduced? How will it be distributed?

Watch this space.

This, then, is an opportunity to think through some 'old' arguments. Why, and in what way, should the government fund film? The UKFC and its advocates seem to be almost completely incapable of making an argument that does not come down to a commercial logic: we invest money into the film industry which has been a growth area of the UK economy. They always represented the perceived interests of the industry players more than the public, or most individual film-makers, who were required to work within a framework that emphasised commercial potential at the expense of everything else. Well, commercial logic has come back to bite them: propping up the banking sector is clearly more valuable to the economy than propping up the film industry. But defending public subsidy at a time like this requires arguments based on other reasons, cultural reasons, political reasons, moral reasons, for example. It is these arguments, more than any others, that can sustain opposition to the ConDems plans for the Big Society (which looks increasingly like 'there is no such thing as society') and judging by the comments on the 'Save the UKFC' Facebook group it is these arguments that motivate most people to defend the UKFC as well.

So is this the death of the UK film industry? A return to the bad old days of Thatcher and the almost complete collapse of British film production? The government's announcement is that it will establish a more direct relationship with the BFI and the Regional Screen Agencies are apprently safe, for the moment. This would seem to be a return to the state of things pre-UKFC with a modest film-culture infrastructure. But is the BFI now capable of fulfilling this role, particularly in terms of production?

The devil, as always, is in the detail. The key questions are: how much will overall subsidy be reduced? How will it be distributed?

Watch this space.

Wednesday, 6 January 2010

MONTAGU'S NEW YEAR

Posted by

MONTAGU

We live in interesting times.

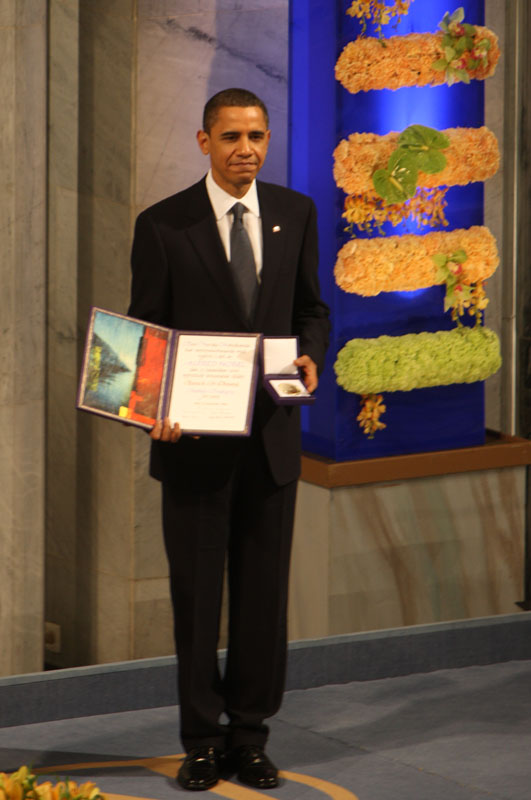

Last year a political victory for a party opposed to free speech and democracy was claimed as a victory for free speech and democracy. Banks demanded the largest nationalisation in history. The Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to a man in control of the largest war machine the world has ever known, currently engaged in war and occupation on three fronts.

What are the key issues for the start of the new decade? How might film-makers respond?

War, Climate Change and Obama

2009 began with a 22 day assault on Gaza by Isreali forces, killing at least 1300 people, the majority of them civilians. The attack was, apparently, timed so as to not interfere with Obama's inauguration. They need not have worried: a year later the era of 'change' promised by Obama has seemed remarkably similar to the Bush era. We begin the new decade with US corporate-imperialism perhaps not as optimistic as ten years ago but still dominant, shaken but hegemonic nonetheless. This was illustrated most clearly by the shambles that was the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference. As Naomi Klein puts it, "There are very few US presidents who have squandered as many once-in-a-generation opportunities as Obama." This does not bode well for the rest of us.

Will the Copenhagen disaster persuade people that our current political system is incapable of solving the problem of climate change? For Mumia Abu-Jamal, Copenhagen means that “it's impossible to resist the suspicion that politics can provide no solution to the serious environmental and ecological problems facing the earth.” However, while this suspicion might be increasingly obvious, it does not, of course, mean it is impossible to resist. We shall see.

Fascism, Industrial Struggle and the Tories

British fascism is on the rise, developing a high media profile in 2009. The BNP dominated headlines around Nick Griffin’s inclusion in a Question Time debate and there have been fascist marches through several major British cities (although so far they seem to have received a well deserved kicking).

Meanwhile the attacks on British workers in the wake of the recession continued. There were signs of a fightback - the most high profile of which was the postal strike, which ended with a whimper, an apparent Union climb-down.

It seems safe to bet on the Tories winning the next election. What real difference will this make? Both parties are committed to cutting public sector spending, to maintaining the UK economy's dependence on the financial sector, to the increasing encroachment of the private sector into public services, to Britain's junior partnership in the American empire. Mandelson's current attitude to Higher Education is indicative of a whole series of entirely opportunistic attempts to further align the state with the supposed needs of business. There is no reason to expect Labour to change if, through some unimaginable turn of events, they win. Would these aims be any different under the Tories? Probably not. The question is, then, how well placed the election leaves either party: how easily and effectively they can push through their agenda; how events effect the strength of political opposition.

At the same time the prospect of a Tory victory must be terrifying for many working within the public sector. If the differences between Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson are anything to go by we can expect the sort of social, educational and cultural programmes that the Tories generally consider liberal and profligate to be first under the cosh. Cultural conservatism, latent racism, reationary gender politics, elitism: all will have space to expand. They have palpable negative effects.

The trajectory of British politics is towards the Right. How might film and media respond?

Political Film and Media in Britain

During these interesting times, where are the film-makers? Where are the critics?

In earlier, equally interesting times - during the 1930s, the 1950s and early 1960s, the late 1970s and 1980s - film-making and film culture was part of the political landscape, not merely documenting the tensions and conflicts of British society but participating in them. In the contemporary scene, save a few individuals, there is no coherent political film culture and no politicised film commentary. Why does British film culture seem to have rejected a direct engagement with political activity?

In the past, these links have been created by politicised film-makers. Most often they made films outside the mainstream. So where is the independent, political, social, radical film sector?

The biggest joke of 2009?

Last year a political victory for a party opposed to free speech and democracy was claimed as a victory for free speech and democracy. Banks demanded the largest nationalisation in history. The Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to a man in control of the largest war machine the world has ever known, currently engaged in war and occupation on three fronts.

What are the key issues for the start of the new decade? How might film-makers respond?

War, Climate Change and Obama

2009 began with a 22 day assault on Gaza by Isreali forces, killing at least 1300 people, the majority of them civilians. The attack was, apparently, timed so as to not interfere with Obama's inauguration. They need not have worried: a year later the era of 'change' promised by Obama has seemed remarkably similar to the Bush era. We begin the new decade with US corporate-imperialism perhaps not as optimistic as ten years ago but still dominant, shaken but hegemonic nonetheless. This was illustrated most clearly by the shambles that was the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference. As Naomi Klein puts it, "There are very few US presidents who have squandered as many once-in-a-generation opportunities as Obama." This does not bode well for the rest of us.

Will the Copenhagen disaster persuade people that our current political system is incapable of solving the problem of climate change? For Mumia Abu-Jamal, Copenhagen means that “it's impossible to resist the suspicion that politics can provide no solution to the serious environmental and ecological problems facing the earth.” However, while this suspicion might be increasingly obvious, it does not, of course, mean it is impossible to resist. We shall see.

Fascism, Industrial Struggle and the Tories

British fascism is on the rise, developing a high media profile in 2009. The BNP dominated headlines around Nick Griffin’s inclusion in a Question Time debate and there have been fascist marches through several major British cities (although so far they seem to have received a well deserved kicking).

Meanwhile the attacks on British workers in the wake of the recession continued. There were signs of a fightback - the most high profile of which was the postal strike, which ended with a whimper, an apparent Union climb-down.

It seems safe to bet on the Tories winning the next election. What real difference will this make? Both parties are committed to cutting public sector spending, to maintaining the UK economy's dependence on the financial sector, to the increasing encroachment of the private sector into public services, to Britain's junior partnership in the American empire. Mandelson's current attitude to Higher Education is indicative of a whole series of entirely opportunistic attempts to further align the state with the supposed needs of business. There is no reason to expect Labour to change if, through some unimaginable turn of events, they win. Would these aims be any different under the Tories? Probably not. The question is, then, how well placed the election leaves either party: how easily and effectively they can push through their agenda; how events effect the strength of political opposition.

At the same time the prospect of a Tory victory must be terrifying for many working within the public sector. If the differences between Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson are anything to go by we can expect the sort of social, educational and cultural programmes that the Tories generally consider liberal and profligate to be first under the cosh. Cultural conservatism, latent racism, reationary gender politics, elitism: all will have space to expand. They have palpable negative effects.

The trajectory of British politics is towards the Right. How might film and media respond?

Political Film and Media in Britain

During these interesting times, where are the film-makers? Where are the critics?

In earlier, equally interesting times - during the 1930s, the 1950s and early 1960s, the late 1970s and 1980s - film-making and film culture was part of the political landscape, not merely documenting the tensions and conflicts of British society but participating in them. In the contemporary scene, save a few individuals, there is no coherent political film culture and no politicised film commentary. Why does British film culture seem to have rejected a direct engagement with political activity?

In the past, these links have been created by politicised film-makers. Most often they made films outside the mainstream. So where is the independent, political, social, radical film sector?

The biggest joke of 2009?

Do you agree?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)