We live in interesting times.

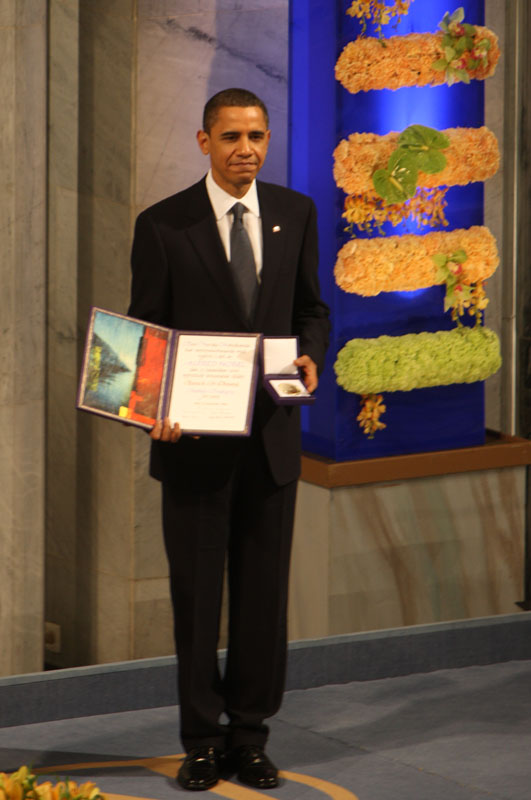

Last year a political victory for a party opposed to free speech and democracy was claimed as a victory for free speech and democracy. Banks demanded the largest nationalisation in history. The Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to a man in control of the largest war machine the world has ever known, currently engaged in war and occupation on three fronts.

What are the key issues for the start of the new decade? How might film-makers respond?

War, Climate Change and Obama

2009 began with a 22 day assault on Gaza by Isreali forces, killing at least 1300 people, the majority of them civilians. The attack was, apparently, timed so as to not interfere with Obama's inauguration. They need not have worried: a year later the era of 'change' promised by Obama has seemed remarkably similar to the Bush era. We begin the new decade with US corporate-imperialism perhaps not as optimistic as ten years ago but still dominant, shaken but hegemonic nonetheless. This was illustrated most clearly by the shambles that was the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference. As Naomi Klein puts it, "There are very few US presidents who have squandered as many once-in-a-generation opportunities as Obama." This does not bode well for the rest of us.

Will the Copenhagen disaster persuade people that our current political system is incapable of solving the problem of climate change? For Mumia Abu-Jamal, Copenhagen means that “it's impossible to resist the suspicion that politics can provide no solution to the serious environmental and ecological problems facing the earth.” However, while this suspicion might be increasingly obvious, it does not, of course, mean it is impossible to resist. We shall see.

Fascism, Industrial Struggle and the Tories

British fascism is on the rise, developing a high media profile in 2009. The BNP dominated headlines around Nick Griffin’s inclusion in a Question Time debate and there have been fascist marches through several major British cities (although so far they seem to have received a well deserved kicking).

Meanwhile the attacks on British workers in the wake of the recession continued. There were signs of a fightback - the most high profile of which was the postal strike, which ended with a whimper, an apparent Union climb-down.

It seems safe to bet on the Tories winning the next election. What real difference will this make? Both parties are committed to cutting public sector spending, to maintaining the UK economy's dependence on the financial sector, to the increasing encroachment of the private sector into public services, to Britain's junior partnership in the American empire. Mandelson's current attitude to Higher Education is indicative of a whole series of entirely opportunistic attempts to further align the state with the supposed needs of business. There is no reason to expect Labour to change if, through some unimaginable turn of events, they win. Would these aims be any different under the Tories? Probably not. The question is, then, how well placed the election leaves either party: how easily and effectively they can push through their agenda; how events effect the strength of political opposition.

At the same time the prospect of a Tory victory must be terrifying for many working within the public sector. If the differences between Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson are anything to go by we can expect the sort of social, educational and cultural programmes that the Tories generally consider liberal and profligate to be first under the cosh. Cultural conservatism, latent racism, reationary gender politics, elitism: all will have space to expand. They have palpable negative effects.

The trajectory of British politics is towards the Right. How might film and media respond?

Political Film and Media in Britain

During these interesting times, where are the film-makers? Where are the critics?

In earlier, equally interesting times - during the 1930s, the 1950s and early 1960s, the late 1970s and 1980s - film-making and film culture was part of the political landscape, not merely documenting the tensions and conflicts of British society but participating in them. In the contemporary scene, save a few individuals, there is no coherent political film culture and no politicised film commentary. Why does British film culture seem to have rejected a direct engagement with political activity?

In the past, these links have been created by politicised film-makers. Most often they made films outside the mainstream. So where is the independent, political, social, radical film sector?

The biggest joke of 2009?

Last year a political victory for a party opposed to free speech and democracy was claimed as a victory for free speech and democracy. Banks demanded the largest nationalisation in history. The Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to a man in control of the largest war machine the world has ever known, currently engaged in war and occupation on three fronts.

What are the key issues for the start of the new decade? How might film-makers respond?

War, Climate Change and Obama

2009 began with a 22 day assault on Gaza by Isreali forces, killing at least 1300 people, the majority of them civilians. The attack was, apparently, timed so as to not interfere with Obama's inauguration. They need not have worried: a year later the era of 'change' promised by Obama has seemed remarkably similar to the Bush era. We begin the new decade with US corporate-imperialism perhaps not as optimistic as ten years ago but still dominant, shaken but hegemonic nonetheless. This was illustrated most clearly by the shambles that was the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference. As Naomi Klein puts it, "There are very few US presidents who have squandered as many once-in-a-generation opportunities as Obama." This does not bode well for the rest of us.

Will the Copenhagen disaster persuade people that our current political system is incapable of solving the problem of climate change? For Mumia Abu-Jamal, Copenhagen means that “it's impossible to resist the suspicion that politics can provide no solution to the serious environmental and ecological problems facing the earth.” However, while this suspicion might be increasingly obvious, it does not, of course, mean it is impossible to resist. We shall see.

Fascism, Industrial Struggle and the Tories

British fascism is on the rise, developing a high media profile in 2009. The BNP dominated headlines around Nick Griffin’s inclusion in a Question Time debate and there have been fascist marches through several major British cities (although so far they seem to have received a well deserved kicking).

Meanwhile the attacks on British workers in the wake of the recession continued. There were signs of a fightback - the most high profile of which was the postal strike, which ended with a whimper, an apparent Union climb-down.

It seems safe to bet on the Tories winning the next election. What real difference will this make? Both parties are committed to cutting public sector spending, to maintaining the UK economy's dependence on the financial sector, to the increasing encroachment of the private sector into public services, to Britain's junior partnership in the American empire. Mandelson's current attitude to Higher Education is indicative of a whole series of entirely opportunistic attempts to further align the state with the supposed needs of business. There is no reason to expect Labour to change if, through some unimaginable turn of events, they win. Would these aims be any different under the Tories? Probably not. The question is, then, how well placed the election leaves either party: how easily and effectively they can push through their agenda; how events effect the strength of political opposition.

At the same time the prospect of a Tory victory must be terrifying for many working within the public sector. If the differences between Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson are anything to go by we can expect the sort of social, educational and cultural programmes that the Tories generally consider liberal and profligate to be first under the cosh. Cultural conservatism, latent racism, reationary gender politics, elitism: all will have space to expand. They have palpable negative effects.

The trajectory of British politics is towards the Right. How might film and media respond?

Political Film and Media in Britain

During these interesting times, where are the film-makers? Where are the critics?

In earlier, equally interesting times - during the 1930s, the 1950s and early 1960s, the late 1970s and 1980s - film-making and film culture was part of the political landscape, not merely documenting the tensions and conflicts of British society but participating in them. In the contemporary scene, save a few individuals, there is no coherent political film culture and no politicised film commentary. Why does British film culture seem to have rejected a direct engagement with political activity?

In the past, these links have been created by politicised film-makers. Most often they made films outside the mainstream. So where is the independent, political, social, radical film sector?

The biggest joke of 2009?

Do you agree?

No comments:

Post a Comment